THE SPANISH armoured vehicles were dug into the side of the road into Oppdal, a mountain village some 300km north of Oslo, cannons pointed across the snowy valley. Their task was to defend the local airport from the might of the “North Force”, played mostly by American marines, whose fleet of tanks assembled at a nearby petrol station. Rifle-wielding marines decked in snow camouflage prepared for battle with cups of hot chocolate, the attendant unfazed by the firepower massing on her forecourt. Yellow-jacketed umpires followed the combat, decreeing whether a tank had strayed into a notional minefield or been struck by hypothetical artillery. “It’s pretty much like battleships,” said Second-Lieutenant Larry Boyd.

The sparring was part of Trident Juncture 2018, NATO’s biggest military exercise since the cold war, lasting from October 25th to November 7th. The alliance is flourishing on the ground, building up forces, transforming its institutions and squaring up to Russia with confidence. The question is whether this progress can be quarantined from the transatlantic squabbling between political leaders.

The very premise of the exercise—an invasion of Norway, causing the alliance to invoke its Article 5 mutual-defence clause—was a signal that, after decades of fighting ragtag Balkan armies and Afghan guerrillas, NATO is back in the business of defending its home territory. The exercise, officials coyly insisted, was “not directed against any country”. But Lieutenant Boyd was clear that his marines were preparing to fight a “near peer” adversary. He did not have to spell out whom he had in mind.

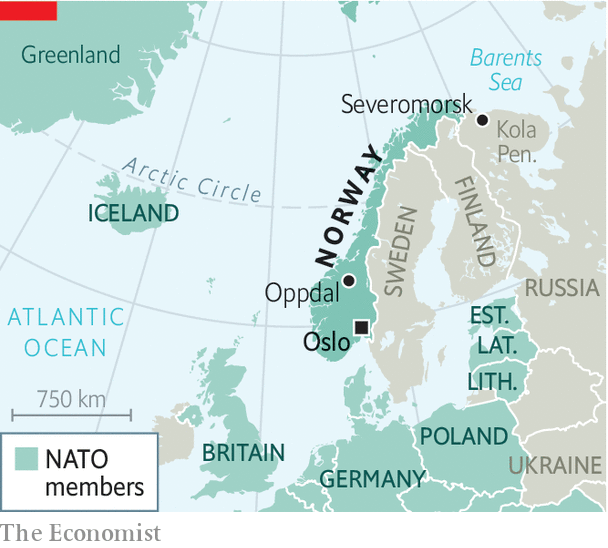

A second message lay in the exercise’s scope, stretching from Iceland in the west to the airspace of non-NATO Finland in the east. The last big war game was held three years ago in Spain, thousands of kilometres from Russian soil. Norway, by contrast, is not only a front-line ally, sharing a 200km border with Russia, but has also watched nervously as Russia’s Northern Fleet, headquartered across the Barents Sea on the Kola Peninsula, has piled up new ships and increased submarine patrols tenfold. That has forced NATO to reacquaint itself with cold war concepts like the “GIUK gap”, a maritime choke-point between Greenland, Iceland and Britain that is Russia’s principal outlet to the Atlantic. Russia has also reoccupied seven former Soviet bases in the Arctic region and launched its first military icebreaker in 40 years. In turn, America has doubled the number of marines based in Norway, and on October 19th sent an aircraft-carrier into the Arctic circle for the first time in almost 30 years.

A third distinctive element of Trident Juncture was its size: 65 ships, 250 aircraft, 10,000 vehicles and 50,000 personnel. This was a test of NATO’s ability to pump reinforcements over the oceans, teeming with Russian submarines, and then across the continent. This has proven tricky. Lieutenant-General Ben Hodges, who retired as commander of American forces in Europe in December 2017, recalls his surprise at learning that Europe’s Schengen Area, which has abolished border controls, did not extend to the free movement of arms. Others point to problems with infrastructure, such as incompatible railway gauges and weak bridges.

NATO’s response to the new threats has been the biggest overhaul of its command structure in a generation. Two new headquarters, one focused on the Atlantic, based in America, and another on logistics, in Germany, will be established over the next three years, adding 1,200 personnel. Generals are also getting chummy with Eurocrats. EU-NATO relations were once “trench warfare”, says Sir Adam Thomson, Britain’s envoy to NATO from 2014 to 2016. Now there is “unprecedented practical collaboration”. The EU published its own action plan on military mobility in March and sent the head of its military staff on a joint tour of Washington with his NATO counterpart last week.

NATO’s renaissance should cheer fans of the beleaguered liberal order. In recent years the alliance has deployed four battlegroups (up to 1,400 troops each) to Poland and the Baltic states as tripwire forces; created a rapid-response brigade (about 5,000 strong) that can mobilise within two days; and committed to having 30 battalions, 30 warships and 30 air squadrons ready to fight at 30 days’ notice. America is spending $6bn a year on its European Deterrence Initiative, lavished on everything from Hungarian air bases to exercises such as Trident Juncture. Russia’s spree of invasion, intimidation and assassination has roused the alliance from its slumber.

Yet this military revival is accompanied by political malaise. For one thing, no one these days is quite sure whether the alliance’s principal member would actually show up to fight in a crisis. The platoon of Montenegrin infantrymen at Trident Juncture, part of the Spanish battalion defending Oppdal, might reasonably have recalled President Donald Trump’s scorn for their “very aggressive” country during this year’s NATO summit, and asked how it squared with the transatlantic spirit on display in the Norwegian hills.

On November 6th, France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, lamented the absence of a “true European army” to “protect ourselves against China, Russia and even the United States”. Yet despite the EU’s new defence schemes, which cover everything from joint arms production to co-operation on military radios, its ambition is far lower than Mr Macron’s language would suggest. Far from supplanting America’s military capabilities, Europe’s national armies are only just getting round to rebuilding their own, hollowed out after the cold war. The EU’s central and eastern European allies, like Poland and Estonia, are horrified by Mr Macron’s talk of protection against America. For all its troubles, NATO remains the only serious game in town.